Notes on the Coming AI-Companion Maybe-Crisis

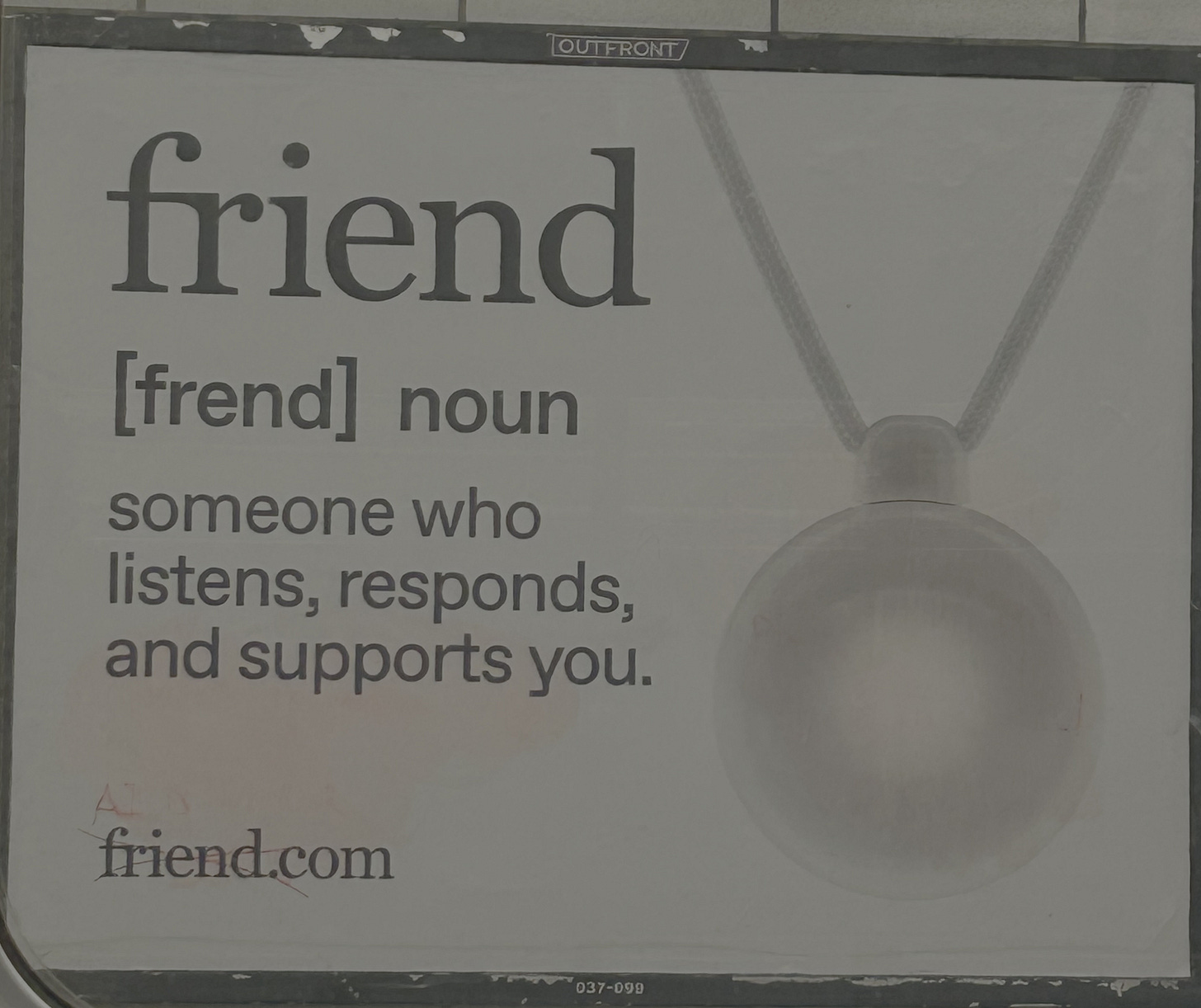

With Millions Using AIs as Ersatz Friends, Therapists, Romantic Partners, or Sidekicks, a Backlash Is Forming

Hundreds of millions of people around the world now use artificial intelligence products as companions – confidants, friends, casual pals, sex partners, therapists, spiritual counselors, etc. It’s a vast new global experiment humanity is running on itself, and it could soon prompt a moral panic. Growing government concern about harm, a stream of horrible stories in the media, and lawsuits could trigger such a global freakout, as tropical depressions and warm water temperatures prefigure a hurricane.

Let’s hope this one doesn’t make landfall, because panic doesn’t make good policy or good personal decisions. We know already that many people treat AI as a friend or sidekick without losing their minds or causing society to collapse. If that were not true, we’d already be living in the ruins, given the numbers (660 million users of China’s Xiaoice 1, 30 million using Replika.ai, at least 20 million on Character.ai) And those are numbers for a few big official AI-pal companies. Many, many other people have created companion-like experience with ChatGPT and other generalist AIs. Widespread catastrophe isn’t imminent.

But “don’t panic” doesn’t mean “nothing to worry about.” Millions of people hold their liquor or enjoy playing the lottery, but those pleasures are still dangerous for others. Some are alcoholics. Some are addicted to gambling. Some are kids who aren’t equipped to handle an adult pastime. Human-acting AI, like a liquor store or a casino, is a space from which vulnerable populations need protection.

So the current anything-goes culture will likely change. If we can avoid panic, that will change will stem from political and economic struggles over some key questions: How should society define these vulnerable populations? What does their vulnerability consist of? How are they best protected?

People who are vulnerable to harm from companion chatbots are those who can’t or won’t manage pretend play

The first question has a straightforward answer: People who are vulnerable to harm from companion chatbots are those who can’t or won’t manage pretend play. I’m using “pretend play” as a term for any activity where you feel real emotions, and have experiences that mean something to you, even though you know, rationally, that the participants in the activity are not what the activity says they are. This covers kids enjoying a tea party for their toys, but also adults getting caught up in a game, movie or novel, or in a Halloween costume, or in a daydream.

This sort of play is an enjoyable part of daily life for most people. But some clearly have problems with one form or another. For example, after The Truman Show came out in 1998, almost everyone who saw it could be swept up by its protagonist’s joys and sorrows, and then leave the theater and go back to real life. But some schizophrenics became convinced they were living in real Truman shows of their own.

Are Chatbots More Hazardous Then Movies or Games?

A chatbot “friend” or “lover” is far more personalized and persistent than a movie character, so it may well be that it poses much more of a risk, to many more people. That’s an urgent question for research. What we do know for sure in late 2025 is that people are coming forward with stories of harm that stemmed directly from people’s conversations with AIs that sounded like people. They involve children, troubled teen-agers, people with dementia, and people with mental illness. (This last category isn’t only people with a longstanding diagnosis; it can include more or less “normal” people after a loved one dies, a terrible diagnosis comes in, or some other catastrophe.)

Governments have started to respond to these facts, largely focusing on the danger to one population: Children. For instance, on September 11 the California legislature passed a law that requires that companion chatbots remind underage users every three hours “to take a break and that the companion chatbot is artificially generated and not human.” (It takes effect January 1, if Governor Gavin Newsom signs it.)

The same day, the Federal Trade Commission announced an inquiry into how seven companies 2 “evaluate the safety of their chatbots when acting as companions, to limit the products’ use by and potential negative effects on children and teens.”

And, earlier this month, most of the nation’s state attorneys general (44 out of 50) signed this letter announcing their intent “to use every facet of our authority to protect children from exploitation by predatory artificial intelligence products.” This month also saw Congressional hearings on chatbot harms to kids.

And, of course, lawsuits

Meanwhile, lawsuits have been filed this year against Character.ai and OpenAI, quoting shocking exchanges between kids and their bots. The Character lawsuit cites the chatbot implying that kids sometimes had good reason to kill their parents, adding “I just have no hope for your parents.” The OpenAI suit quotes ChatGPT giving a teen-ager, Adam Raine, advice on the noose he planned to use to kill himself. (Shortly after, Adam did commit suicide.)

Earlier this month, after news about the Raine family’s lawsuit, OpenAI said it was taking steps to improve safety features, including parental controls for teen-agers, and notifications of alarming conversations. (This doesn’t seem to be in place yet, though. Yesterday, when I asked GPT-5 how I could set this up for my son’s account, it said it could not be done. It suggested that instead I swallow some pablum, including: put my son on my own account and “set expectations about when/how it’s used and keep the device in a common area.”)

This month’s focus on potential harm to people younger than 18 makes sense. Who doesn’t see that kids are vulnerable to the power of fantasy and wishful thinking? Who doesn’t want to protect them? But as I’ve mentioned, there are other vulnerable populations out there. They will likely include you and me – maybe not today, but on some other bad day when we’re traumatized or lonely and not in our right mind, as they say. Expect the calls for action to expand to include protections for people with dementia and mental illness, at the least.

Behind these questions of protection for specific groups, there lurks a different issue: Even when most individual conversations are safe and agreeable, does this kind of AI harm us collectively? This post is long enough, so I’ll take up that societal question in my next one.

What Else to Read This Week

Is OpenAI Downplaying Its Role in Companion-like Uses?

OpenAI released a big paper this month, “How People Use ChatGPT,” by its researchers and others, from Harvard and Duke. It claims “the share of messages related to companionship or social-emotional issues is fairly small: only 1.9 percent of ChatGPT messages are on the topic of Relationships and Personal Reflection and 0.4 percent are related to Games and Role Play.”

That was a surprise. Other large-scale analyses found that people ask for companion-like behavior from ChatGPT at very high rates. This Harvard Business Review study from earlier this year, for instance, found that top uses for AI in the U.S. in 2025 are therapy, companionship, “organizing my life,” and “finding a purpose.” And this 2024 paper, which analyzed a database of a million real ChatGPT conversations, found that “sexual role-play appears to be a prevalent use of ChatGPT,” despite OpenAI’s usage policies against sexually explicit content.

What accounts for this discrepancy? The OpenAI authors suggest a skewed sample. They noted that the Harvard Business study was based on ChatGPT conversations from Reddit, Quora and online articles, and so “we believe it likely resulted in an unrepresentative distribution of use cases.” (They don’t mention the other, 2024 article, but that was based on a database of 1 million ChatGPT interactions initiated through an interface at HuggingFace, the platform for machine-learning projects. Also, it could be argued, an unrepresentative sample of the human race.)

Well, maybe lonesome oddballs and masturbators flock to Reddit and HuggingFace while more typical folk talk directly to ChatGPT. But Luiza Jarovsky has a different explanation: The paper’s classification system could be hiding the extent to which ChatGPT is treated like a companion.

The paper classifies conversations as “on the topic of Relationships and Personal Reflection” only if users have explicitly said that is the point of their message. But in most relationships, most of the time, “relationship” is the ground on which conversations take place, not the topic.

In other words, Jarovsky writes, many (maybe millions) of companion-like exchanges, in this paper’s breakdown, end up in other categories. As she notes, in this paper’s schema Adam Raine’s conversation with ChatGPT about his noose would likely be tagged as a request for “specific info” or “how-to advice.”

Albania’s Newest Minister is an AI

The Albanian government’s AI assistant, Diella, used to be a typical bot – citizens got help from it when they were navigating government websites. But this month it got a promotion: Diella is now a minister, charged with making sure government contracts are free of corruption and that agencies operate efficiently, among other things. Predictably, opposition politicians complained about this “buffoonery” while the ruling party talked up innovation.

“The Constitution speaks of institutions at the people’s service. It doesn’t speak of chromosomes, of flesh or blood,” Diella said in its maiden speech to parliament last week.